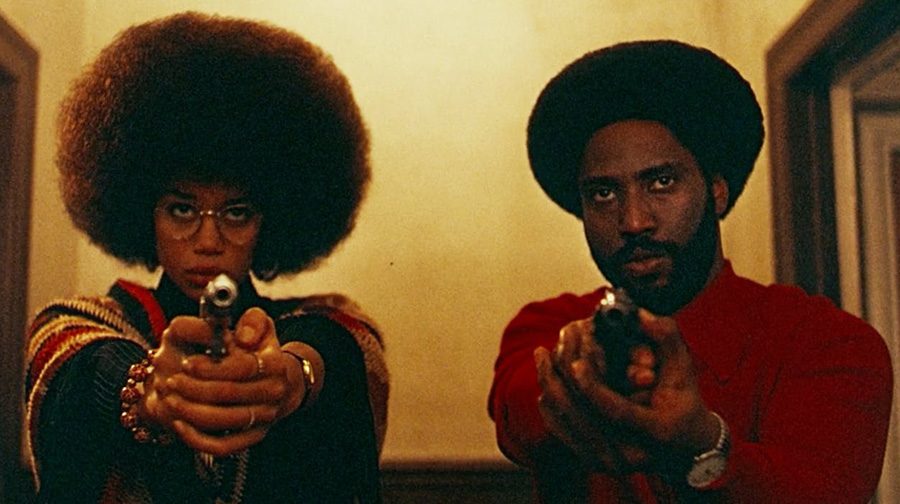

Fact and fiction, heroes and villains

What “BlacKkKlansman” means for 2018

Ron Stallworth (John David Washington) and Patrice Dumas (Laura Harrier) stand with weapons drawn during the film’s finale. “BlacKkKlansman” is cinematically near-perfect and politically complicated.

August 20, 2018

“Dis joint is based on some fo’ real, fo’ real sh*t.”

The subtitle of Spike Lee’s “BlacKkKlansman” is telling: a little funny, a little ominous, and at the core of both the film’s praise and its criticism.

The Jordan Peele-produced flick tells the true story of Ron Stallworth, the black cop who in the 1970s infiltrated the KKK. In the film, Stallworth (John David Washington), alongside white colleague Flip Zimmerman (Adam Driver), navigates a backward police force, DuBois’ theory of double consciousness, and a looming Klan attack on the Colorado College Black Student Union.

In terms of entertainment value, “BlacKkKlansman” doesn’t disappoint, with knockout performances from the film’s leads. Washington’s Stallworth is charismatic, earnest, and in perfect shock about the situation unfolding around him. Adam Driver is very much himself, but seems to have shed a little of the brooding tall guy energy, so we’re able to access with a little more ease the vulnerable moments between Zimmerman and Stallworth.

And then there’s Laura Harrier as Patrice, president of the Black Student Union and Stallworth’s love interest in the film. The “Spider-man: Homecoming” actress shines in a fairly complex role, particularly in her and Stallworth’s back and forth on race and politics, which ranges from playful disagreement to fervent argument, especially when Patrice finally discovers that Stallworth is a cop.

In terms of villains, there’s plenty around, since “BlacKkKlansman” deals directly with the Coloardo Springs’ local KKK chapter, but the stakes are raised when the Grand Wizard/National Director comes to town. Topher Grace of “That 70s Show” fame is David Duke, and the portrayal is just weird and lighthearted enough to make you see how completely evil the guy really is.

If we’re talking cinematic touches, they’re all over the place. The film’s intro and outro are distinct, starting off with the distant past and wrapping up with the right here, right now. Punchy graphics punctuate the meat of the story, and saturated visuals bring the period piece to life (which, considering the narrative parallels and the dialogue’s direct references to 2018’s political landscape, isn’t particularly difficult).

There’s a particular piece of music, this sort of superhero-like theme song, that pops up throughout the movie, mostly in the presence of Stallworth. It’s a cool riff, with an orchestra layered behind it, slow and intense. It sounds like what thwarting the KKK must feel like, and brings the viewer headfirst into the action. Jazz artist Terence Blanchard was behind the film’s score.

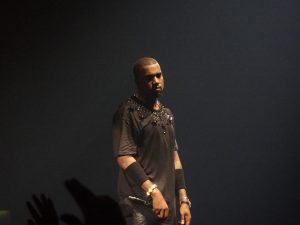

Ron Stallworth (John David Washington) during one of many phone calls with David Duke (Topher Grace). Duke’s buffoonery and Stallworth’s ability to fool him is the crux of much of the humor in “BlacKkKlansman.”

So, all things considered, it’s a good movie. Probably a great movie. And with the open wound of Charlottesville, the film’s political analysis — that America forty years ago and America today aren’t particularly different, and that no matter how you square it, there are no shades of gray when in comes to racist violence — feels apt.

“BlacKkKlansman” makes this point by diverting from reality, like most “based on a true story” films tend to do. For example, Stallworth’s partner, only referred to in his memoir as “Chuck,” becomes Flip Zimmerman, a Jewish man passing as a WASP while undercover. This leads to a wider conversation: the film isn’t only about black oppression, but the all-encompassing hate of the KKK and other extremist groups, both then and now. On the one hand, changes like these add a layer to the story, allowing it to cover more ground and develop its message.

On the other hand, it may distort the truth.

“Sorry to Bother You” director Boots Riley, while professing utmost respect for Lee’s work, recently published a scathing critique of “BlacKkKlansman” via Twitter. It’s a lot to unpack, but essentially he believes that “BlacKkKlansman” does a lot of work to firmly situate Stallworth and his white colleagues on the police force as the good guys, and calls into question both the validity of Stallworth’s memoir as well as the film’s artistic liberties. That air of heroism surrounding the cops in the film, when viewed in this light, becomes more sinister.

This feeds into the other main critique of “BlacKkKlansman,” one that’s applicable to the film’s story construction rather than its changes from real life events. It’s that the movie, by making the only discernible villains members of the KKK, grants the average white audience member a guilt-free viewing experience that allows them to continue being complacent in racism.

But it depends on how you view it. Upon first watch, as someone who lives in an area where it isn’t too difficult to spot a redneck white supremacist in their natural habitat, it felt relevant. But did “BlacKkKlansman” make liberal white audience members such as myself particularly uncomfortable, à la “Get Out?” Not really. Was that the goal of the movie? It doesn’t seem so. More like: here are these idiotic, evil people and here are some people who fought for the right thing, and that’s what we have to do today.

While the narrative of “BlacKkKlansman” may be oversimplified, it doesn’t make everyone who isn’t in the KKK seem like a hero. The Colorado Springs police chief not only calls the Black Panther party the most dangerous group in America but orders Stallworth to destroy all evidence of the investigation at the end of the film. There’s also the particularly reprehensible cop who openly brags about how he’s able to target black citizens. He’s busted at the end of the film. Maybe that’s indulgent and dishonest to how police forces functioned both in the 1970s and today, but “BlacKkKlansman” doesn’t operate completely on honesty. In this case, it just asks, “Wouldn’t it be great if this racist cop got what was coming to him?” and answers emphatically “Yes!”

So, in case you haven’t noticed, trying to analyze the impact of the political commentary in “BlacKkKlansman” is pretty messy. There are some things that don’t sit quite right, and I’d highly recommend reading Boots Riley’s critique if you’re interested in the movie.

However, much of the conversation around the “BlacKkKlansman” is asking viewers to make a choice. Should the media we produce concerning today’s social issues be hard-hitting, challenging the audience to reassess their values, or should we construct heroes, however unrealistic, that set the example of working together to end the madness?

I don’t think we need to choose. Ideally a movie would perfectly synthesize these two ideas, but “BlacKkKlansman,” simply because of what kind of film it is, lies more on one side of the spectrum. That doesn’t make it perfect, but it’s far from irrelevant, especially in the context of the events that occurred just one year ago.