Aesthetic obsession bites director’s thematic expectations

Indian Paintbrush, American Empirical Pictures

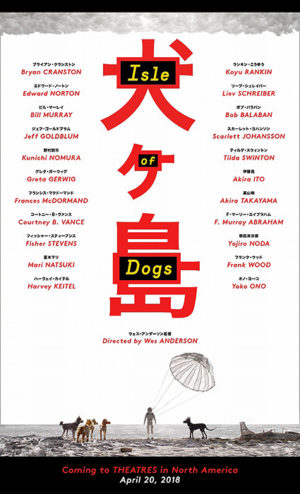

The young boy at the center of “Isle of Dogs,” Atari Kobayashi, surrounded by the furry friends he makes along the way. While visually engaging, “Isle of Dogs” not only presented a lackluster story but has found itself at the center of a heated debate regarding media and culture.

April 19, 2018

“Whatever happened to man’s best friend?”

So is the earnest query of “Isle of Dogs.”

In our most odd modern society, dogs have increasingly become something prized and even idolized — a feat that becomes easier when they have someone to run their Instagram.

Media including these furry friends seems to be rooted in why dogs are so loved: their sheer cuteness and the emotional bonds we form with them. Wes Anderson’s newest flick continues to play on this obsession with canines— even placing the homonyms “Isle of Dogs” and “I Love Dogs” at the core of the film’s social media ad campaign— but with some noticeable twists. Now the dogs are the outcasts, banished from the futuristic Japanese metropolis Megasaki to live on Trash Island, and the oftentimes literal dog-eat-dog world that is created serves as a grim reminder of where can dogs end up when outside the warm embrace of human care.

The new film is notable as Anderson’s second whirl at an animation feature, the first being the acclaimed “Fantastic Mr. Fox.” “Isle of Dogs” certainly follows its predecessor with grace in terms of craftsmanship, although it leaves much to be desired with regards to telling a worthwhile story. Layer that with the seemingly arbitrary selection of Japan as a setting, and you’ve got a perfect recipe for a heated discussion among movie lovers about the politics of Wes Anderson.

The film begins by explaining dogs’ fall from grace in Japanese society. The main culprit is the Kobayashi clan: notorious cat-lovers who flood the country’s power structure and begin to peddle anti-dog propaganda. Accelerating forward in time, Megasaki’s very own demagogue, Mayor Kobayashi, signs a decree to send all dogs to Trash Island, the main justification being the rapidly spreading dog flu. His only opposition comes from student activists, who rally behind Professor Watanabe of the Science Party. But the fear-mongering has taken root, and the decree is subsequently put into effect. Little does the mayor know, however, his own ward and distant nephew Atari is distraught at the decree and the taking of his dog Spots. It’s this boy’s love for his dog that drives the plot and serves the only chance at emotional depth for “Isle of Dogs.”

Next we meet a pack of dogs that will eventually witness Atari crash land on Trash Island. They are all reasonably fun to watch, but they also blend together with staggering ease despite the familiarity of the celebrity voice actors (including Bryan Cranston and Jeff Goldblum). The only dog pertinent to the plot is Chief, a black shaggy-haired stray whom Atari gets to know better on their way to find Spots.

“Isle of Dogs” is a visual marvel. There’s an earnest attention to detail, a quintessential component of any Wes Anderson film. It makes for nice moments. And while these images do create an impression in the minds of viewers, it’s not nearly enough to be truly memorable. Here’s why.

(Oh, and before we get into the not-so-good stuff, it feels obligatory to say that I’m not a dog person. I’m still impartial to the crusades of Mayor Kobayashi but certainly not heart-eyes for them, either).

The dogs, aside from the translator and an exchange student, are the only characters in “Isle of Dogs” that speak English. This may have aimed to create a sense of closeness with the animals for English-speaking audiences, but since the dogs rarely vary from gruff monotone, it’s hard to work up genuine worry about them. They seem able to handle themselves just fine, and there isn’t much emotion at all regarding wanting to leave Trash Island. The dogs just say they want to, and then do that. The dogs in “Isle of Dogs” have the nuance of thought of actual dogs, and that (surprise!) doesn’t make for good storytelling.

It does leave room, however, to appreciate the main character that we can’t understand. Atari, a twelve-year-old with a habit of incessant teeth-chattering, has much less screen time than his canine counterparts and somehow carried just as much if not more impact. Since Atari’s devotion to his pet and sympathy for Chief have so much weight, it would make sense that Chief’s arc would be satisfying by extension. That doesn’t end up being the case.

Chief’s story is compromised by this crazy uncomfortable dog romance. Near the beginning of the film, he meets a purebred dog, Nutmeg. Nutmeg’s entire conception as a character is next-level bonkers because she’s weirdly sexualized. Is someone going to tell Wes Anderson that almost every human being is guilty of misgendering dogs, so outfitting her to be so obviously female is kind of… creepy? Anderson doesn’t seem to have a problem incorporating realism when it means violence among dogs, but he somehow feels alright about injecting stereotypes from one species into another as if it makes perfect sense.

And that’s not even the nail in the coffin. At the end of the film, Chief explains to Nutmeg that he doesn’t know why he bites, indicating he hasn’t swayed much from his pattern of aggression. Nutmeg responds that she is “not attracted to tame animals.” So Chief’s arc is wrapped up there with some cheap joke, and it doesn’t even make sense. Wasn’t Chief getting to know Atari supposed to be an end to his rough ways? Wasn’t Chief supposed to evolve? Apparently, Wes Anderson isn’t sure, and it leaves the audience hopelessly confused about the moral leanings of the film’s hero.

So the consensus is pretty predictable, given Anderson’s past work. “Isle of Dogs” is fun to watch and full of eclectic characters (honorable mentions go to Professor Watanabe’s assistant Yoko Ono and the pro-dog hacktivist that was probably the guy to be cheering for all along), but it’s ultimately not satisfying. And no one’s asking for “Isle of Dogs” to be some life-altering masterpiece, just merely that it mean something.

(Except it doesn’t end there.)

It’s unclear why Wes Anderson chose Japan as a setting, and many critics are putting the director under fire for that, accusing the film of perpetuating “orientalism,” or demeaning and stereotyping Asian culture. Showcasing other cultures just because they make a great package for your cheeky animated flick isn’t exactly honorable. And since the Japanese language is more of a device to help viewers identify with the dogs, there’s not even much of an invitation for multicultural engagement. Looking at “Isle of Dogs” through this lens becomes increasingly damning, as what appeared to be light-hearted examinations of another culture carry more of an edge, and characters like American exchange student Tracy Walker start to smell vaguely of white savior.

This isn’t great news from “Isle of Dogs,” regardless of which side of the discourse you’re on. Its one big asset, the visuals, is under high suspicion of merely aestheticizing Japanese culture. The characters and story simply refuse to pack an emotional punch, and so mention of “Isle of Dogs” may be restricted to think pieces, and any hope of merit as an artistic work may well begin to fade away.