Bible as Literature class constricts students’ cultural awareness

The Mill’s new Bible as Literature course will be available for students to take next year and will be taught by English teacher Shad Genovese. Unfortunately, this class has to potential to promote Christian-centric views and limit students’ global awareness. A course studying religious texts as literature would be more beneficial because it will teach all the same sills while opening students’ minds and broadening their cultural awareness.

May 13, 2016

Starr’s Mill is smack in the middle of Georgia, nestled in the depths of the Bible Belt. Students are accustomed to seeing churches on every corner and have grown up with pre-game prayers and Christian-based clubs as the norm.

Christianity and the contents of the Bible are nothing new to a majority of students, either because of their own religious backgrounds or simply by being aware of the Christian-centric culture surrounding them.

Starting next year, the Mill will be feeding into this culture by offering the new Bible as Literature course taught by English teacher Shad Genovese.

Genovese justifies this class by explaining that “there are three things that influence western philosophy, more specifically literature,” Genovese said, “and the Bible is one of them.”

No one can refute the claim that the Bible is one of the most influential works of literature of all time. Allusions to the Bible can be seen in almost all works of western literature, and the understanding of the text is important to analyze modern culture and world history.

If English teachers already dote on Shakespeare, which Genovese cites as the second most influential force to western philosophy, then some would assert that students should also learn about the Bible.

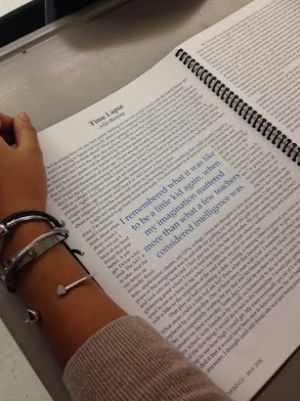

This is true, but what about other important religious texts? Studying the Old and New Testament as literature will benefit students through improving their critical thinking skills, testing their discussion civility and allowing them a holistic understanding of other works. But in doing so, it will ignore other religions and cultures.

“It’s very much a critical thinking, critical reading [class],” Genovese said. “How do we make connections, why are there massive wars in the Middle East, how has [the Bible] influenced literature and art and why?”

Yet these connections could be furthered by having a class with a broader topic such as a class studying religious texts as literature.

Education should expand awareness instead of promote Christian-centrism, and a class encompassing other religious texts would allow students to think critically, discuss civilly, and understand other literature better than the Bible as Literature course.

It’s the classic concept of a confirmation bias. People want to be proven right, not wrong. Fayette County has a Christian culture, and people want school to reinforce biases, teach their already-established beliefs and divide Christian students from other global ideals and culture.

Would a class studying non-Christian religious texts as literature even be approved as a class?

“If a certain demographic, like let’s say someone in Fayette County really wanted to teach the Quran, this class does not exclude that class from happening,” Genovese said.

The reality is people don’t seem to want to expand past western and Christian values. Signs staked in April on Redwine Road north of the school indicate the one-sided mindset, claiming that Common Core standards emphasize Islam too much.

In south Nashville, parents are putting in complaints that middle school Common Core standards are indoctrinating students and portraying Islam as a “naturally peaceful religion.”

Williamson County, Tennessee is “overwhelmingly white, Christian, and Republican,” similar to the culture of Fayette County. These protests against Common Core have become nationally recognized, and all evidence indicates Fayette residents would have the same reaction to a class about Islam or the Quran.

If the academic discussion of an eastern religion is so threatening to people they want to scrap all of Common Core, then why is the Bible different? Why aren’t people having the same adverse reaction to a whole class dedicated to the Bible as they do to one unit on Islam?

This closed mindset is threatening to the modern globalized world, and students need diversification, both in Tennessee and in Georgia, to be part of their education.

The tentative syllabus seems like it will be comprehensive by exploring “the Bible’s literary techniques and its enormous variety of genres as well as the historical periods that produced and are reflected in it.” Performance standards set by the state require students to understand the text and its cultural value, discuss translations and acknowledge the Bible’s influence on history and government.

But what looks good on paper doesn’t always translate into the classroom. The class will still be taught through the lens of Christian values and stories, again only confirming beliefs instead of broadening students’ scopes.

There are guidelines to ensure a secular teaching style, but students don’t have to follow these same guidelines in discussions.

“I mean, I think that there will be debates [on religion], but I don’t think that will be the focus of the class,” prospective student junior Ashley Broderick said. “I think it would be more of the kids who would try to bring that stuff up than the teacher.”

Students and teachers all have unconscious biases, and this factor, considering a majority come from a Christian background, must be considered when evaluating the class.

The simple truth is that the Mill doesn’t have the right climate for this class. There’s no doubt that Genovese has a plan to keep the class as open as possible, but that doesn’t mean students will have the same mindset.

“As for the class itself,” Genovese said, “what kids do with it, I don’t know if I can really control that.”

The Bible Belt is founded on tradition and known for “strong attachments to their churches,” being “generally more socially conservative,” and “resistant to change.” There’s a strong possibility that this class will be a vehicle to further promote Christianity through the students taking it.

“If they want to think religiously about it and offer that point, they can,” Genovese said. “I’m not going to condone it or say that’s the rule, nor will you be graded based on your belief system.” He said the Georgia code has guidelines intended to promote civil discourse between students, but Genovese also acknowledged how quickly discussions in his just core literature classes dissolve into yelling matches.

Starr’s Mill students will benefit from the Bible as Literature class, but studying all religious texts as literature would use the same skills and broaden their cultural scope. Students here aren’t exposed to other faiths or cultures daily, and school should be a place where they become more aware of other religions.

Instead of playing up the current Christian-centric culture and honing in on the Bible, the Mill should be offering a class that opens minds to other religions and allows students an understanding of other cultures as well as their own.