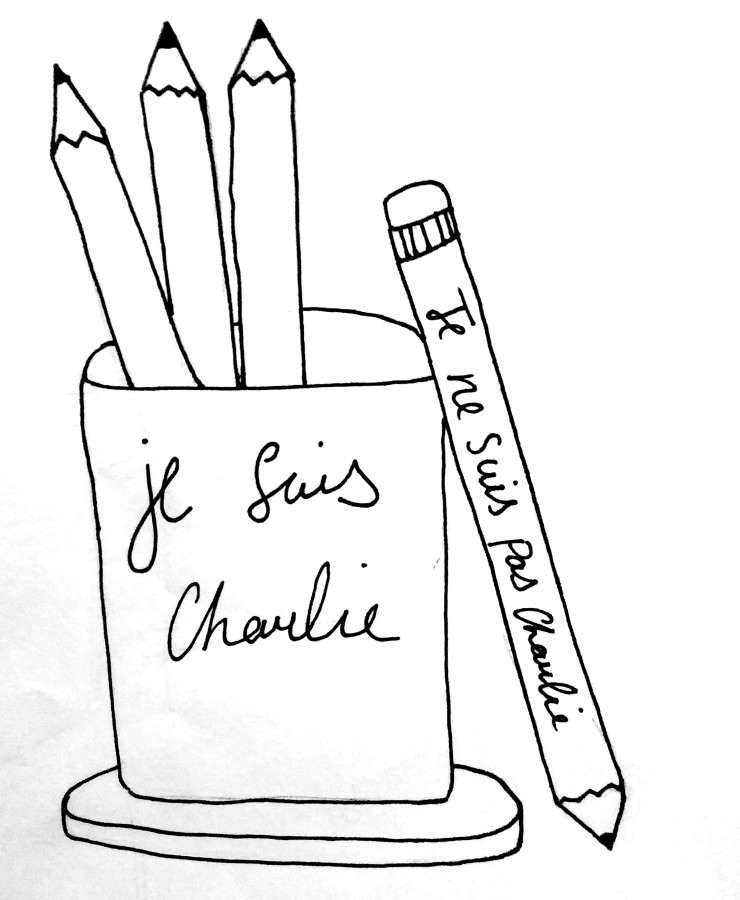

Je ne suis pas Charlie

February 5, 2015

About two weeks ago, The Prowler staff gathered for a photo. We all held up pencils, an image shared on social media by countless others around the world to show support for journalistic freedom of expression in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks in Paris. People everywhere posted photos of themselves carrying banners and signs emblazoned with a common sentence, je suis Charlie.

On Jan. 7, the offices of the French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo in central Paris were attacked by two gunmen, both with histories of involvement in militant Islamic groups, the BBC News reported. Twelve members of the Charlie Hebdo staff were killed, along with a policeman who was responding to the scene. Within two days, both attackers were dead. On Jan 8., a gunman sympathetic to the Charlie Hebdo attackers carried out an attack at a kosher supermarket in a Jewish neighborhood in Paris, which resulted in the deaths of the gunman, four civilians and another police officer.

Why? These attackers disagreed with the magazine’s representations of the Muslim faith, particularly its cartoon depictions of the Prophet Muhammad.

After this tragedy, the people of France struggled for ways to stay strong. The hashtag “#JeSuisCharlie,” French for “I am Charlie,” began to trend on Twitter as millions took to the Internet and to the streets to demonstrate their support for Charlie Hebdo and freedom of the press. Pencils symbolized the old adage that “the pen is mightier than the sword.”

Even though the events that unfolded in Paris were horrific and undeniably tragic, I did not participate in our staff photo at The Prowler. Instead, I set my pencil down and walked out of the frame. I did not want to be Charlie Hebdo. I knew that because I know France’s history. This movement was about more than just the rights of the press.

France owned the north African nation of Algeria until 1962 when nationalist forces won their independence. Many indigenous Algerians who had been loyal to France immigrated there soon after. Other north African colonists joined, bringing their Islamic faith with them. According to the Pew Research Center, modern-day France has a Muslim population of nearly 5 million, the highest in western Europe.

Unfortunately, France also has a complex history of religious intolerance. Because of an upsurge in anti-semitism, 2014 saw almost 7,000 Jews leave France for Israel. This was double the previous year’s figure, according to statistics from the Israeli government. The burqa, a religious head covering worn by some Muslim women, has been banned across the nation. And since the Charlie Hebdo attack, The Independent, a British liberal newspaper, reports that 26 mosques throughout France have been attacked with bombs, bullets and even pig heads. According to the New York Times, a pregnant Muslim woman was recently assaulted in a French suburb for wearing a veil, and subsequently she lost her baby. The current climate in France has many Muslims afraid to leave their homes and risk being attacked even though they are French citizens with no ties to the shootings or the extremists.

This is why I cannot be Charlie. Of course, I condemn terrorism. I believe in freedom of the press and agree that “the pen is mightier than the sword.” But I feel uncomfortable showing solidarity with a magazine that has perpetuated negative stereotypes of Muslims and helped feed France’s Islamophobia. I’m worried that the sentence “je suis Charlie” is being used to justify attacks on Muslims around the world.

One member of the staff asked me if I declined to be in the photo because I was afraid for my own personal safety. This caught me by surprise. The idea that I would have to worry about being attacked because I declared my support of the magazine is ridiculous. I am lucky enough to live in a country where I have law enforcement officials keeping me safe and a constitution allowing me freedom of speech. I am part of neither an ethnic nor religious minority and don’t have to face any fear of persecution for my opinions. Holding a pencil and saying “I am Charlie” requires no bravery on my part. The declaration feels almost hollow.

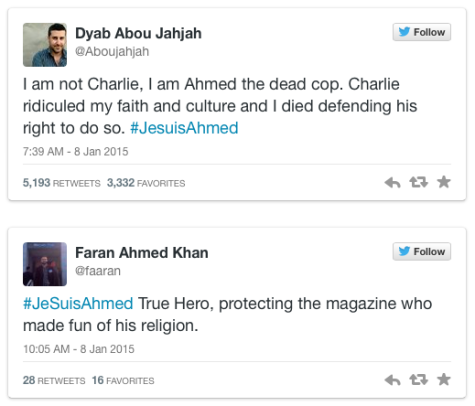

One of the policemen killed was Ahmed Merabet, a Muslim. When some heard of this, they began a new tag on Twitter: “#JeSuisAhmed.” Despite France’s history of religious intolerance, Merabet still chose to become a police officer and protect the rights of French citizens. Ultimately, he died defending a magazine that has repeatedly mocked his faith and culture.

Merabet’s story perfectly illustrates the idea that French philosopher Voltaire once expressed. He said, “I do not agree with what you have to say, but I’ll defend to the death your right to say it.” While I may not be Charlie, I recognize how important freedom of the press is, and I recognize the evils of terrorism. But I also recognize how dangerous this solidarity movement could be.

The je suis Charlie movement simplifies the meaning of freedom of the press by glorifying a controversial magazine. Showing respect for those who died and for their rights does not require showing respect for the material they publish. I can stand for freedom of the press without directly supporting Charlie Hebdo. The magazine has a right to publish anything it wants, but it must also be prepared for criticism and backlash. The magazine publishes material that opens the door for attacks on Muslims.

So for now, je ne suis pas Charlie. I am not Charlie although I do want to protect the freedom of the press. I just don’t want the freedoms of Muslims to be crushed in the process.