Student requests fall on deaf ears

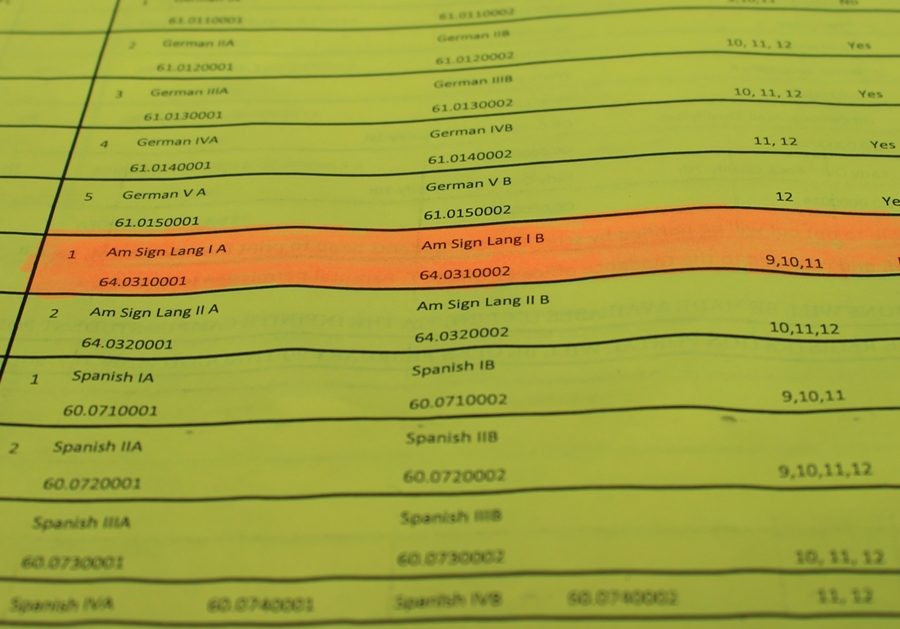

Starr’s Mill has offered an American Sign Language 1 class since 2015. However, this year, even with the course on the student course request sheet (pictured here), 96 students missed the opportunity to take ASL because an agreement could not be reached on how the course would be funded.

October 18, 2016

Nearly 100 students–gifted students, regular education students, students with disabilities–all register to take a forensic science class listed on the student course request sheet. The students want another option for a science class other than environmental science or human anatomy. They meet with their counselors, they hear positive feedback from previous students, and they look forward to the opportunities taking the course may create. When the next year begins, they are informed that the course is not being offered that year.

This is exactly what happened with the American Sign Language 1 class this year at Starr’s Mill High School. Nearly 100 students selected ASL 1 as a preferred or alternate elective, but when the year began, the course was no longer an option and they had to seek a different elective option.

Starr’s Mill High School houses the Deaf and Hard of Hearing Program for the Fayette County School Corporation. Eighteen students from all over the county are transported to Starr’s Mill where they receive an inclusive education and additional services relevant to their hearing needs. Starr’s Mill provides these students with a least restrictive environment under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act.

Two years ago, Starr’s Mill introduced an American Sign Language 1 class in order to offer students an additional world language (then referred to as “foreign language”) opportunity. ASL is a system of communication using visual gestures and signs that helps people with hearing impairments. ASL joined Spanish, French, and German as world language course offerings at Starr’s Mill. Acquiring permission and actually offering the course faced some struggles.

When the idea for the ASL classes was first introduced, only students with an Individualized Education Program could take ASL. However, due to parent complaints on the first day of school, Assistant Superintendent of Student Achievement Dr. Terry Oatts opened the class to all students. As a result, in the spring of 2015, Starr’s Mill had 152 students signed up for ASL 1 even though it had not been advertised.

Part of the course’s initial popularity was attributed to the benefits the course offered. Those benefits extend beyond deaf students. According to documents Karneboge uses to discuss the program, “ASL promotes a culturally diverse classroom, encourages awareness of students with disabilities, and creates a tolerance for various learning styles.” Plus, ASL utilizes teaching methods for students who are visual learners.

“It’s [ASL] a good class because there’s a lot of kids who are visual, not auditory, learners,” Karneboge said.

The benefits extend beyond the Mill. Ten of the twenty students currently taking ASL 2 now have an additional pathway for a career to pursue in college.

With so many benefits, why was no class created for the 2016-2017 school year?

“I was told it was a funding issue, so like who would pay for the class,” American Sign Language teacher Julie Karneboge said.

Some argue that because the original intent of the course was to serve students with disabilities and the course is taught by a special education teacher that Exceptional Children’s Services should provide funding for the position. “Ultimately, it is not my place to determine language offerings at our high schools. Dr. Portia Rhodes is the coordinator who works with world languages, and Dr. Terry Oatts approves course offerings,” director of Exceptional Children’s Services Rosie Gwin said.

However, Oatts sees it as more of a local, building-level decision. “The Principal in consultation with the Registrar has to make decisions at the school level about what courses will be offered based upon the requests and the availability of a properly certified teacher to teach those courses,” Oatts said.

Principal Allen Leonard offers a different perspective. “I go to the county every year at the proper time when they [the county] are deciding about the budget, [to say] here is what I like to offer and this is the staff that I need to be able to do that,” Leonard said. “Sign Language is a little bit of a challenge because sign language teachers rarely teach anything else. There are certain number of classes [that the school] can offer.”

Gwin, Oatts, and Leonard may not agree on who should provide the funding necessary to offer the course, but they all agree on the value of offering ASL as a world language.

“I think having sign language as a world language class… is very valuable. One of the usable languages we [the school] can offer,” said Leonard.

“The class allows their peers to learn to communicate better with students who use ASL as their mode of communication. In addition, we need sign language interpreters, and this class might help build interest in that career path,” Gwin said.

“ASL is officially a world language, and as a district, we value affording our students a viable world language pathway,” Oatts said.