Demanding honesty at Starr’s Mill

Rounding of grades raises potential ethical concerns

Although it is not a written rule or policy at Starr’s Mill, teachers have been known to round students’ final semester grades from 69% to 70%. This practice raises questions regarding the honesty and ethics of some teachers at the Mill.

October 25, 2017

At Starr’s Mill High School grades are taken very seriously. The importance of succeeding is clearly seen in Starr’s Mill’s history of high test scores and passing/graduation rates.

The vision statement at Starr’s Mill is “to maximize individuals’ talent, achievements, and character in a safe environment.” However, an issue that could affect these elements in each student’s educational experience at the Mill is the rounding of grades.

Grading is a very intricate system that is the deciding factor of many things, such as earning credits and graduating. Therefore, grades must be accurately evaluated and logged by teachers to show the correct student information.

In cases at Starr’s Mill, teachers have been known to round students’ grades, particularly from a 69 percent to a 70 as a final semester average because it has been said that a policy was in place to do so. However, the difference between the two grades means much more than a single point. Bumping the grade from a 69 to 70 could give a student a credit for that class. However, if that credit means the student graduates, Starr’s Mill’s graduation rates will also change.

“Grades are a very subjective thing,” Principal Allen Leonard said. “Teachers are the ones that we ultimately trust as professionals to determine those grades, and if the teacher feels like the student has earned that grade, we’re going to trust that teacher to determine it.”

At Starr’s Mill, teachers are given the leeway to use their judgment to determine each student’s grades. They use their training and experience to interpret each student’s grades, which makes grading a subjective thing, despite the desire for it to be as objective or as fact-based as possible. However, after adding in components such as essays and projects, teachers use their judgement, making grading more of an interpretation question than honesty.

Leonard stands behind the idea of letting teachers handle the grading of students and trusts them to evaluate students correctly. He negated the policy of no final grades of 69% by stating, “There is not a rule that requires any of our teachers to not give any particular numbers or anything like that.” He only encourages all teachers to double-check student grades if they happen to be on the border of major grade differences. If the grade is truly and correctly recorded, then students can receive any number on their report cards.

Starr’s Mill’s registrar Krystin Glover had similar views as Leonard on the subject. She, too, contradicted the possible “no 69%” policy by stating, “It’s actually not a rule at all here or a policy here.” Glover also agrees that teachers are human and can make mistakes when recording grades, and they should make sure they have correctly calculated and recorded the grades when they are on a borderline of major grades. Similar to Leonard, she also believes teachers have the freedom and flexibility in their classrooms to grade how they desire.

Despite there being no written rule or policy that teachers do not have to round student grades from a 69% to 70%, the practice of doing so still remains.

A teacher in the science department is one of the teachers who does not allow students to finish the semester with a 69% because he was told not to by the county. He claimed that the teachers were told to give students extra credit to bump up their grade or double-check previous grades in case a mishap occurred.

Another science teacher also does not allow his students to earn a 69% as a final grade. He believes that if the student is right on the edge of passing the class, he should go back into the gradebook and check if there is anything missing that can be made up in order to bump the grade up to a 70% and passing. However, if there are no missing assignments for a student, the teacher gives the student a 69% as is.

However, a teacher in the math department disagrees. “Teachers shouldn’t be determining [students] grades. They should be calculating them, and there’s a big difference there,” the math teacher said.

This same math teacher, unlike other teachers and administrators, strongly disagrees with the rounding of any grades. He believes that the students determine their own grades, no matter what that number may be, and it should stay that way in the grade book. It is not up to the teachers to decide the grades, but to only calculate and record them. However, he does agree that if a grade borders on a major grade change, such as a 69% to 70%, then the teacher needs to ensure that every grade was recorded correctly in the grade book.

“Changing any grade based on anything other than more grades is grade manipulation, which is unethical,” the math teacher said.

Although classroom practices may differ, the rules regarding the accurate reporting of grades do not.

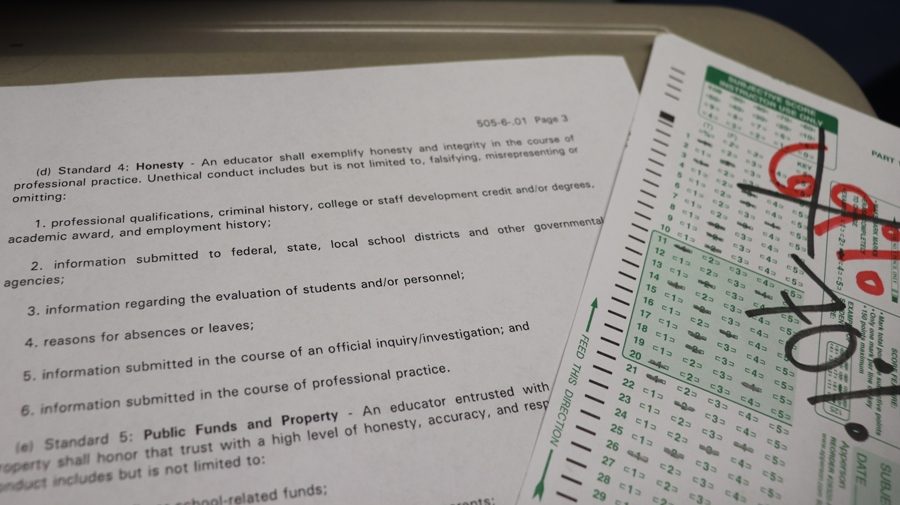

Rules regarding grading students can be found in the Georgia Professional Standards Commission’s Code of Ethics for Educators. The GAPSC “sets and applies guidelines for the preparation, certification, and continued licensing of public educators.”

A part of these guidelines is the Code of Ethics for Educators. This is a set of standards regarding conduct by the education profession. Embedded in this Code of Ethics are guidelines concerning the grading of students.

Standard Four: Honesty, states, “An educator shall exemplify honesty and integrity in the course of professional practice. Unethical conduct includes but is not limited to, falsifying, misinterpreting, or omitting [information].” This information includes the evaluation of students and/or personnel, which involves grades.

Rounding grades could be taken as a violation of the Code of Ethics since educators are supposed to correctly evaluate their students, according to Standard Four.

When contacted, chief investigator John Gant could not answer all questions because a formal complaint had not been made. However, he did state, “if the PSC receives a complaint that an educator violates some rule or regulation or standard involving grading, then the PSC would look at the circumstances involved and make a determination on whether or not it’s a violation of the Code of Ethics.”

Leonard believes that rounding grades is not against the honesty standard of the Code of Ethics because of the subjectivity of grading. He takes into consideration the training and experience of the teachers, trusting them to make the right judgement when grading students.

Glover concludes that simply adding extra points to a student’s grade without reason is discouraged at Starr’s Mill and would be an ethics violation. However, she agrees that students who complete extra credit credit have the opportunity to have their grade raised.

“Any time that a student is going to earn a grade, whether it be a 99 or 79, we want for them to have actually earned that grade,” Glover said.

If one of Starr’s Mill’s goals is to maximize the character of the students, the potentially unethical practice of rounding grades may jeopardize the school’s mission statement and endanger the teaching licenses of its educators.

![Starr’s Mill’s College and Career Ready Performance Index scores raised substantially from 77.3 percent in 2015 to 96.2 percent in 2016. “This growth shows that [Starr’s Mill] is a great place to go to school,” Principal Allen Leonard said.](https://www.theprowlernews.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/IMG_3569-300x200.jpg)

![Principal Allen Leonard poses for a photo in his office on the day of the “Great American Eclipse.” “Safety is number one,” Leonard said. “Number two is making sure that [students] have the proper environment... and the time to be able to accomplish what needs to be done.”](https://www.theprowlernews.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/6241716800_IMG_3417-300x200.jpg)