Putting assessments to the test

Do Fayette County tests and assessments measure up?

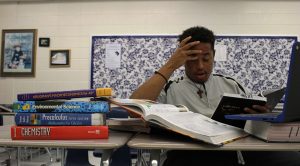

Classroom time provides teachers with the chance to engage with and instruct students. When standardized testing is scheduled, however, unique activities and creative learning opportunities tend to be the first things cut from teachers’ lesson plans.

December 1, 2016

While 180 days may seem like an eternity to a high school student, it is equivalent to less than half a year. Between syllabus days, pep rallies, school assemblies and field trips, how much time are students actively receiving instruction in the classroom? Are mandated assessments the most effective means of testing? Where do schools draw the line and say “enough is enough?”

First and foremost, it is crucial to understand the backbone of both national- and state-level testing before taking a closer look at Fayette County’s decisions and their effect on individual high schools. Superintendent Dr. Joseph Barrow explained the origins of the current testing system in place, tracing it back to the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965. According to the U.S. Department of Education, this act was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson who “believed that ‘full educational opportunity’ should be ‘our first national goal.’” The law set a foundation for funding both the elementary and secondary school levels alongside improving overall quality of education and testing scores.

“It’s been reauthorized several times,” Barrow said. “One of the reauthorizations was No Child Left Behind, which became the Every Student Succeeds Act and Race to the Top under President Obama.” Barrow was an active part in the overdue reauthorization of NCLB, working with educators and officials across the country to pass an updated version of the act. This process allowed them “to ultimately have some influence to get it reauthorized through local and national advocacy with the American Association of School Administrators,” he said.

In order to be in compliance with federal law and to be eligible for funding, Georgia implements mandated statewide assessments, Georgia Milestones, which were formerly the End of Course Tests. According to Barrow, “assessment and accountability are big pieces that trickle down” from the federal level and ultimately shape how testing standards and requirements are set in each state. Eight courses, two from each core subject area, have set “Georgia Milestones” that are required for all Georgia high school students: Coordinate Algebra, Analytic Geometry, United States History, Economics/Business/Free Enterprise, Biology, Physical Science, Ninth Grade Literature and Composition, and American Literature and Composition.

“SLO’s, or Student Learning Objectives, were required for all subject areas that were not tested with a Milestone, which in high school is the vast majority of courses,” Barrow said. Fayette County opted out of Race to the Top when it was given the option back in 2010. The 26 counties in Georgia that decided to join were required to begin SLO testing immediately, but Fayette only just recently began to administer them. Since the guidelines for these tests were not strictly dictated from the state, this form of diagnostic testing varied in structure and content from school district to school district.

“[The Georgia Milestone] is a standardized state assessment, so those subject areas or grades don’t require Student Progress Measures since they are tested with a state required statement,” Dr. Terry Oatts, Fayette’s Assistant Superintendent of Student Achievement, said. “All of the other subjects then are subject under our state’s accountability framework, which is a function of state statutes saying that we have to administer a student growth measure.”

He explained that Senate Bill 364, from the 2015-16 General Assembly session, “supplanted House Bill 244, which required all 180 school districts in Georgia to report scores to the state.” The new law reworked the main function of the SPM, incorporating it into the teacher evaluation process and reducing the number of required classroom observations that principals and assistant principals had to conduct. The diagnostic testing process has now been refocused on the local level, giving greater power to each district in determining what is tested and how. “What our district thought about with input from principals and teachers was that we had refined the process with our SPM to the point that we felt really good about them,” Barrow said. “This way, it would be a useful tool rather than a problematic one.” He specified that Fayette’s SPM is created by groups of teachers selected specifically for their expertise and knowledge in a subject area.

According to Oatts, the rebranded SPMs “allow teachers to ascertain the depth or lack thereof for a particular body of knowledge, informing their particular lesson plans and maximizing instructional planning and delivery,” Oatts said. The “vast majority of courses” that were once required to have an individual course-specific test now allow for districts to “collapse and have one measure per teacher,” he said.

Fayette’s five high schools run on either six or seven period schedules in which students are required to be tested in each of their classes. Students who are taking SPM courses are required to take both a pre- and post-test, and these mandated tests cannot be exempted. The same holds for Milestone tests, which are administered at the end of each semester. “We’ve had some changes in the number [of mandatory tests], which, I believe, have benefited students and teachers by reducing the amount of tests that they must take,” Oatts said.

While strides may have been taken to limit the amount of time students spend testing, there is no denying that it takes up a significant portion of school days. “My hope is that we can somewhat reduce the number of assessments because I know that I’ve heard from teachers and from students and from educators all across the state that we’re spending a lot of time testing, and it’s cutting into our instructional time,” Barrow said. Each of the Fayette County high schools implements its own exam exemption policy based on academics or attendance, allowing students to opt out of taking regular semester exams with the exception of Milestone and AP tests.

Regardless of whether or not a student chooses to take an exam, entire school days and sporadic class periods are dedicated to testing and ultimately take away from time that would otherwise be spent in the classroom.

“I think we’ve already reduced the amount of testing that is done, and the state has allowed us to do that,” Barrow said. “People are trying to figure out what the student knows on a cost effective and fairly consistent basis, and while the testing format that we use, in my opinion, is not the best, it can get to the masses and get some indication.” The Milestone tests are equivalent to semester exams in that they count towards 20 percent of a student’s final semester grade, unlike the SPM post-test that counts for two percent or less of a student’s grade. The discrepancies in grade weighting and equivalencies among the various cumulative and diagnostic tests contribute to the excessive testing tendencies of Fayette’s current system.

All courses, except for the eight Milestone subjects, have exams at the end of the semester, even if they have a respective SPM assessment in place. This doubling up on testing adds to the heap of scantrons and test booklets that students dedicate time to, not to mention the impact it has on teachers. As a result, they must reconfigure lesson plans, unit outlooks and classroom assignments to incorporate testing into their whittled-down 180 days in class.

Testing for the semester exams alone cover a span of eight days, and each Milestone takes up at least half a school day, requiring teachers to relocate rooms and work around interrupted bell schedules. On top of the chaotic scramble to move lesson materials to a different hall or the pain of cramming these lessons into a shorter timeframe, a significant portion of students may miss any given class depending on their grade level and the Milestone subject that is being tested that day.

“I actually think that if assessment or testing is not meaningful or purposeful and intentional, then one could argue that it is encroaching upon instructional time,” Oatts said. “But the reality is that assessment done right does not have a dichotomous relationship with instructional time but is on a continuum. It’s assessment as instruction.”

In addition to Milestones and semester exams, students and teachers alike must spend class time on SPM assessments, which require one or two class periods to complete for both the pre- and post-tests. Students who take AP courses must miss additional class time over a span of two weeks during early to mid May, just around the time that high school classes are submitting last-minute assignments and finalizing grades.

“We’re not done by any stretch,” Barrow said. “You do the best you can in the time you have. You learn from that and hopefully alter your process.” While the amount of time spent testing may be a necessary evil at the moment, the effectiveness and validity of the tests may be called into question. If the Milestones and SPMs are worthy of taking up such a large portion of time that takes students away from traditional learning, it stands to reason that they should be an accurate and meaningful medium of testing that can truly and positively impact both teachers and students in order to progress education and the art of learning.

“There is a subtle term called assessment of learning and assessment for learning,” Barrow said. “Our formal structures now are assessment for learning, and what I’d really like us to focus on are the assessments of learning.” The current diagnostic measures, like most standardized tests, are rather one-size-fits-all in the sense that every student taking them receives the same questions, and progress is based upon accuracy.

“I would really like to look at assessment over testing,” Barrow said. “The assessment of learning can be done relatively easily as a ticket out the door, as a real short method, or as a socratic seminar discussion. It should be more diagnostic and informative so that we can find the gaps and help fill them.”

While the score that a student receives on these assessments that becomes a part of their final grades is based upon accuracy, the SPMs’ true purpose, according to Oatts, is “to determine individual student growth, whereas the purpose of those student growth percentile measures as a state assessment is to compare scores to other students in a similar bracket.”

So how exactly is student growth measured or quantified? “When we talk about student growth at the state level, students are compared to others who have performed similarly on other high stakes tests,” Oatts said. This grouping creates a more even playing field that systematically factors out for variations in student learning and knowledge. “I think that’s real important because you want to compare students who have a similar history,” he said.

Even with differences in student achievement taken into account, the truth lies in Oatts’ admittance that “no accountability framework is perfect.” He goes on to explain that the system currently implemented in Fayette County, while a work in progress, is an “earnest attempt to build and have a better structure than what we had with No Child Left Behind, which only looked at English/Language Arts and Mathematics.”

Behind the SPMs, however, is a perplexing grey area that involves the grading and means of measuring student progress and growth. Merely taking the difference from a student’s final score and his or her original pre-test score, in actuality, reveals very little about this student’s true capacity for potential and retention of relevant knowledge. If he or she scores well above peers on the pretest, there is very little room for improvement on the final. The converse is true in that a student who has very low accuracy on the pretest has a greater possibility for expressing percentage growth.

“For a student who performs very poorly on the pretest, whether by design or because of what they did or didn’t know, and performs very highly at the end, there are fair questions with manipulation or what a student can do to register more growth than another student who may, in fact, be performing better,” Oatts said. The rubric for calculating the Student Growth Percentile is not included in the Teacher Keys Effectiveness System Handbook nor the Teacher Effectiveness Measure Rubric, which are used to determine teacher effectiveness by factoring in student performance and teacher evaluations.

The former Fayette County Coordinator of Assessments and Accountability, Kris Floyd, was in charge of overseeing testing in all five high schools, specifically the SPMs. She just recently retired from the FCBOE system and now works at the Georgia Department of Education. “Floyd would be perfect to bring that up with, especially as a the former testing coordinator and an AP statistics teacher,” Oatts said, deferring questions pertaining to the SPMs’ scoring guidelines to Floyd. “She would be able to describe how the scores are reported and distributed.”

Floyd said that she was not available to be interviewed.

Oatts explained that the SPMs and diagnostic measures could, and should, be used to help shape teachers’ in-class instruction by notifying them as to where their students’ strengths and weaknesses lie. The content of these tests and question-by-question scoring breakdowns, however, do not reach teachers. This leaves a rift between the intended purpose of the SPMs and the ultimate effect it has on students and teachers. “Again, I am going to defer to Mrs. Floyd for the substance of that, but what I will say is that teachers do have access to the results [of SPMs],” Oatts said. “We do have a means through our Student Information System to document student performance.”

On the receiving-end of the results, though, teachers still ultimately lack the information necessary to effectively incorporate what the SPMs test since objective-specific analyses are not provided alongside students’ results and test grades.

In addition to standardized testing and performance assessments, students are subject to take standardized writing assessments implemented at the county level. Fayette County Coordinator of Language Arts and World Languages, Dr. Portia Rhodes, oversees English/Language Arts testing and writings for the middle and high school levels. She explains that county writings date at least a decade back in the Fayette system and have undergone recent changes in both the creation and grading process.

“It’s been on our records for over ten years, and it’s the expectation that we give writing assessments for elementary, middle and high school students,” Rhodes said. “We used to do these assessments twice a year, and they were generated by us, the teachers, alongside department chairs.”

She said that in recent years, however, the writing assessment process “became cumbersome to make topics every year and score them.” Beginning in the Fall semester of the 2016-17 school year, Fayette made the decision to collaborate with the Georgia Center for Assessment through the University of Georgia.

“GCA saw a need to help formatively assess,” Rhodes said. “We gathered middle and high school teachers to view the [GCA] presentation, and each department at the five middle and high schools voted. It wasn’t an isolated decision but rather a collective whole, and from there we moved forward.”

The new “Writing Assesslets” are aligned to the Georgia state standards and have been crafted based on what is required from students through both Milestones and grade level standards. “It measures the same thing that your teachers should be measuring,” Rhodes said. The differentiation between a normal assessment and the GCA “Assesslet” is “something the company came up with,” she said. “Maybe they did that to take the stigma away from assessment and standardized testing because those other tests are summative and these writings are formative.”

While the GCA writings align to English and Language Arts standards, they fall short when it comes to evaluating Literature students’ abilities to analyze literary works. Even though the content of the writing and the content of their courses did not mirror one another, students taking British Literature and AP Literature courses were not exempt from taking the county writing at the beginning of this semester. Rhodes explained that since this was the first time Fayette County decided to work with GCA, all students, regardless of their English course’s content, were expected to take the Assesslet.

“We will give an alternate type of assessment based on literary texts,” Rhodes said, estimating that this alternate writing assessment would take place sometime in January for AP Literature students. “Through meetings with teachers and department chairs, we will devise a test for AP Literature that more closely aligns to its guidelines,” she said.

Unlike the Milestones and SPMs, Rhodes explained that teachers receive a data file with both right and wrong answers for each student’s Assesslet alongside comments and feedback. “The plan is for teachers to go through the data and have conversations with their students,” she said. “It gives students the opportunity to familiarize themselves with the skills of critical reading and citing text, all in a non-threatening environment.”

Another difference with the writings and other mandatory assessments is that the writings do not count for a percentage of students’ semester grades. “It’s more of a ‘I should put my best foot forward’ assessment rather than counting as an exam worth 20 percent,” Rhodes said. “If every student puts forth their best level of work, this can tell us a lot as a grade, school and district. For me as the coordinator, I can look and see where our strengths lie and needs-improvement areas are.”

Rhodes states that, when it comes to Fayette’s English/Language Arts Department, excessive testing is not a concerning issue. “When you budget your time, you can schedule around those tests,” she said. “We have a countywide calendar that is generated by the assessment coordinator, so teachers can look ahead at these dates.”

The quality and purpose of the tests implemented in Fayette County seems to overshadow both the quantity of tests administered and the quantity of days they span across. While students may be spending a significant amount of time with a pencil and scantron, the purpose behind testing through SPMs, Milestones, and other standardized tests is what the county focuses on with student growth and classroom instruction.

“I think that assessment is very important, and for me, it’s not been about assessment per say but the balance,” Oatts said. “Historically it has been an imbalance towards high stakes testing. I’m not anti-high stakes tests but the ratio should be more towards formative rather than high stakes or state-administered tests.”